FLUXSeries

2019–202120 Artworks

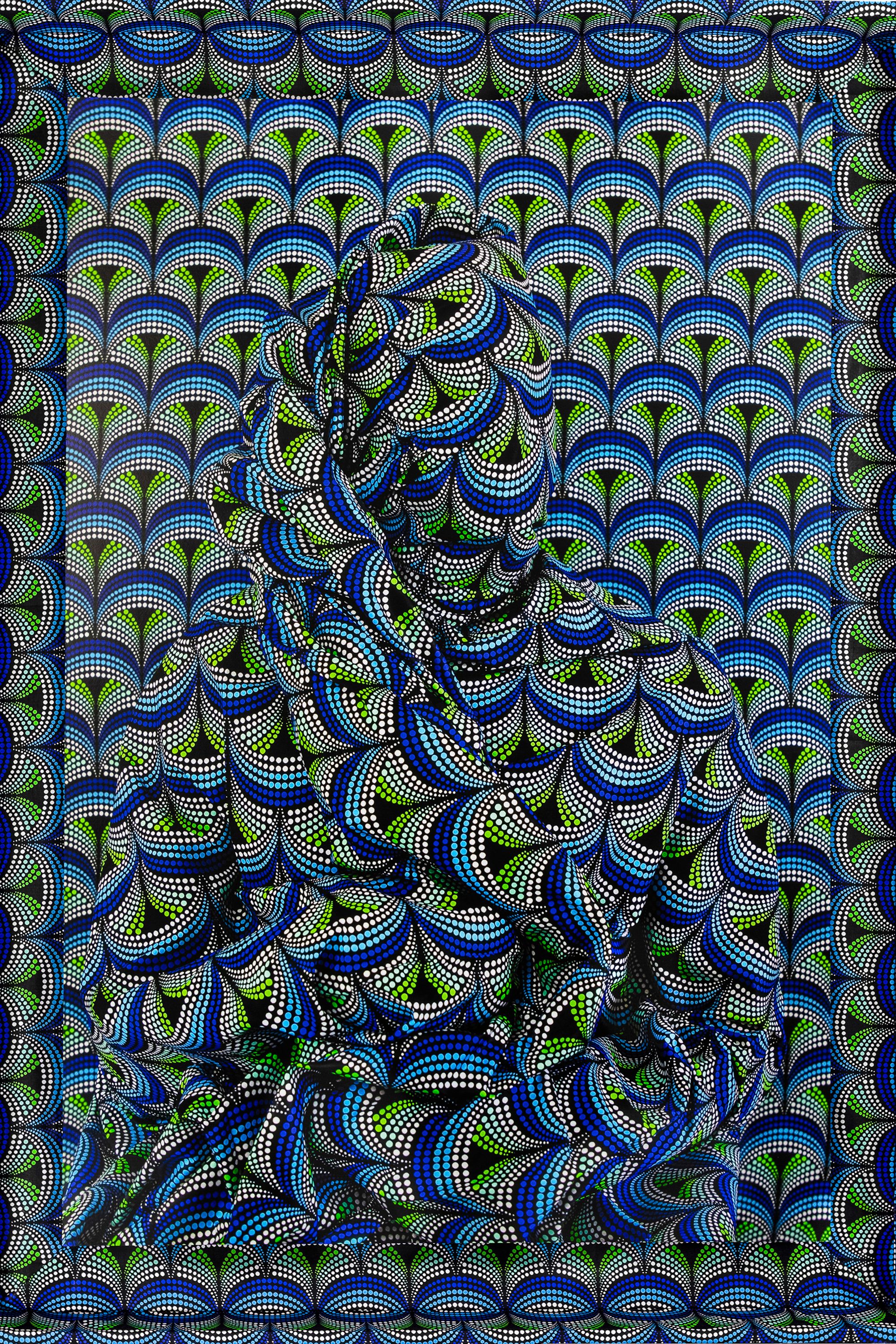

Scales, 2021

While the functional purposes of textile are evident, its indexical capacities are not. FLUX (2019-2021) draws the viewer's attention to the textile as a document in which politics, economics, and histories collide. Focusing specifically on wax print, this series addresses the naming and origin of these textiles. Wax print—a wax-resistant dyeing technique—exists under various monikers, including African wax print, Dutch wax prints, ankara and batik. These names reveal the colonial histories and economic reactions woven into the processes and patterns that define each print; a vibrant aesthetic that obscures the iniquitous past, driving a dynamic narrative that reflects the complex conditions by which these textiles have come into existence.

FLUX is a series of shifting photographic artworks composed of silhouettes that are wrapped and warped by textile, saturated in color and a medley of patterns. Each frame is uniquely upholstered with wax print sourced from Ivory Coast, Senegal, Nigeria and the Netherlands. Some of the images distort visibility while others create hypervisibility, almost negating form into animated camouflage of the body. Outbursts of saturated colors and hyperoptic motifs manifest vibrating effects, obscuring the complex and sometimes iniquitous conditions by which these textiles came into fruition, thus destabilizing their source(s) of origin. This multiple dimensionality creates a kaleidoscope of perspectives, horizontally and vertically. Horizontally, in that the material has come into existence across borders over land and water, and vertically in that they draw from and evoke cosmic, mythical, and religious inspirations. Furthermore, these particular wax prints are an index for mapping the colonial trade routes. While they certainly can be seen as escapist dreamscapes, they are also objects of oppression and capitalism.

In most cases the fabric is defined by its maker, but these fabrics in flux are an exception. Who names them? Is it the entity who produces the cloth, or the entity who consumes it? Or is it, perhaps, the one who ensures their passage to a new geographic coordinate? As one might question whether denim is French or American because of its use of indigo: is it Japanese, Indian, or Ghanaian? One could follow a similar line of questioning the origin of wax print: is it Indian, Chinese, Javanese, Dutch, or West African, and if so, then what part of West Africa, exactly? What is clear is that these particular wax prints present a literal and conceptual space with hidden stories and promised potentiality. They conjure pride and pity, celebration and rejection, power and greed.

While the classification of this cloth is complex, its origins are not. Wax prints have come into existence by a variety of cultures; first seen in India, China, and Java. With the advent of British and Dutch colonial trading in the region, objects, ideas, and humans were traded regularly, and it was by water that this passage would occur. Fabric requires water not only for the growth and harvesting of the fibers and dyeing techniques, but for migration as well. The trans-global trade routes networked across the oceans and seas from Europe, around Africa, along the Arabian coast through South Asia to reach East Asia, and back again.

In the mid-19th century, the Dutch engaged in new technologies to mass-produce wax fabrics for sale on the Javanese market. The look of machine-made batik would appear similar, but ultimately this product was not as refined as the labor-intensive handcrafted textiles made by batik masters in Java. A “crackling” effect would occur in the process, causing the pigment to seep into the fabric in unintended places. While these batiks were rejected in Java, markets on other parts of the trade routes—particularly along the African coastline—embraced them. The fabric fever caught on and today these fabrics are widely found in Ghana, Nigeria, Senegal, Ivory Coast, and Namibia, and yet, to this day, the majority of the design and production takes place in the Netherlands.

These fabrics in flux are a commodity once considered as precious and as commonplace as gold, frankincense, myrrh, jewelry and, as previously mentioned, humans. FLUX questions the very nature of how things are named, how they are translated, and how, eventually, they are reinterpreted. Furthermore, it questions the intention of their production. If it is not for the preservation of heritage, then is it for the propagation of economic wealth? And, for that matter, whose wealth?